From the Archives is a recurring series that highlights Alexandria-Washington’s archives and museum. Visitors are welcome to visit the museum during the memorial’s operating hours.

Alexandria-Washington Lodge, No. 22’s archives contain over 4,000 items related to the history of Freemasonry in Alexandria, Virginia, George Washington, and American history. One of the most important items in our collection is the lodge’s meeting ledgers, which begin in February 1783, during the lodge’s formation, and span well into the twenty-first century. The first set of rules governing the lodge, or bylaws, appears in the earliest meeting ledger. Let’s take a brief look back at the lodge’s first set of rules to better understand how early members conducted their activities and engaged with other Freemasons during this early period of American history.

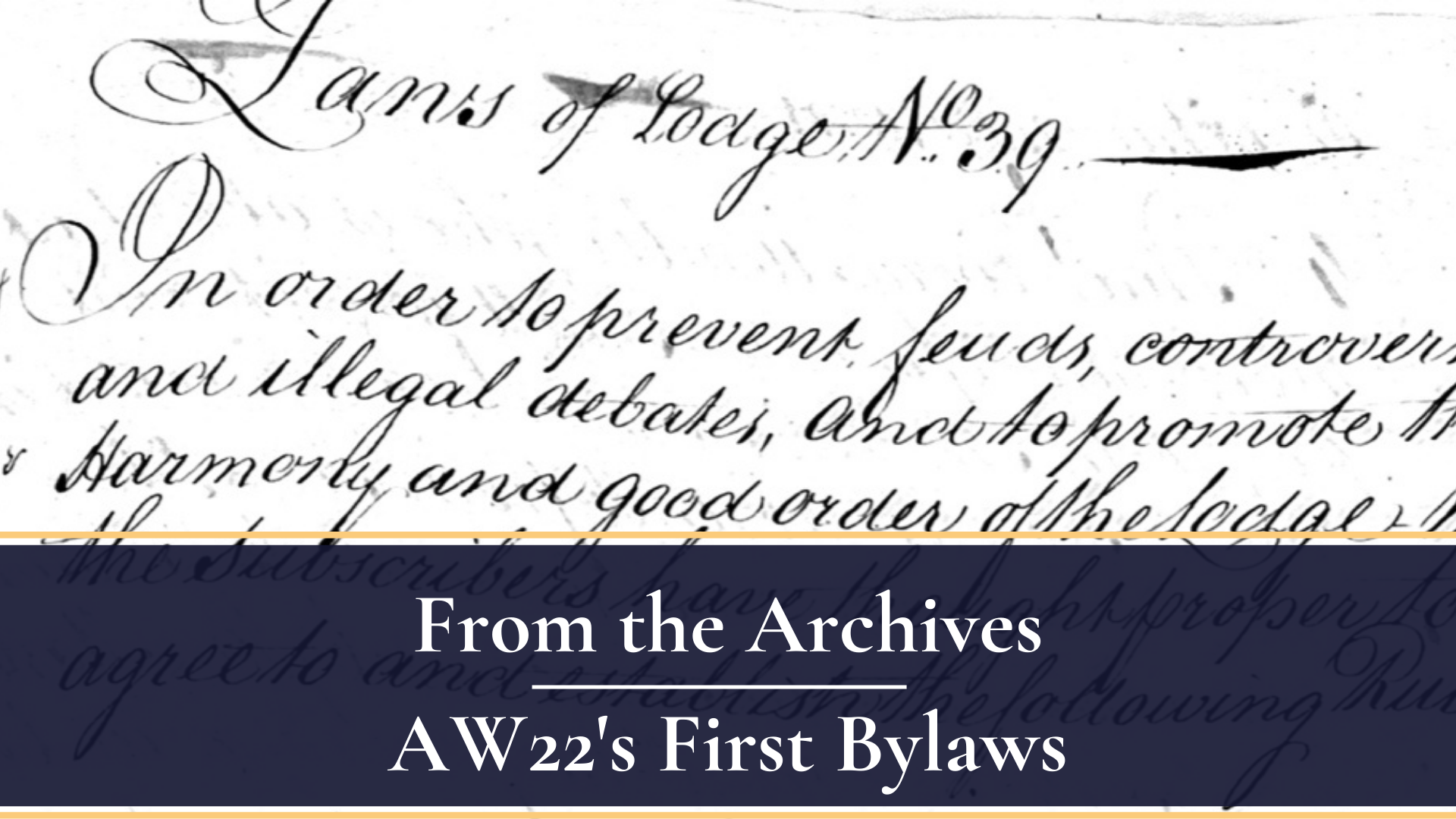

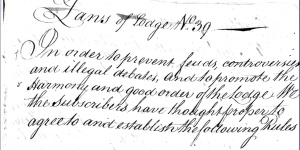

In early 1783, Freemasons from Alexandria petitioned the Provincial Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania for a charter to establish a lodge in their town. Their request was granted on February 3 of that same year and they received a charter to work as Alexandria Lodge No. 39. To form a new lodge the members were required to draft up a set of bylaws, which were written into the secretary’s meeting ledger for reference. The bylaws contained twenty-one numbered articles that outlined lodge governance, fees, and membership duties. As the document’s preamble notes, the bylaws were intended “to prevent feuds, controversies, and illegal debates, and to promote the harmony and good order of the lodge.”

Bylaws Preamble

The first two articles determined the lodge’s meeting date and time. Members met “regularly on the Friday after the third Monday” each month. Evening meetings began promptly at 7 o’clock between March and September and 6 from October and February to account for daylight savings. Meetings are now scheduled for the second Thursday of each month.

Article three detailed the tiler’s duties. In addition to his responsibilities while a lodge is in session, the tiler distributed meeting notices and other correspondence around town. This duty often entrusted him with sensitive and important information concerning lodge affairs. While not explicitly mentioned in the bylaws, tilers often maintained the lodge’s meeting room, prepared refreshments, and ensured the space had enough firewood for winter meetings. Today, most of our communications are performed electronically through email, social media, and membership databases.

Article four required members to attend all meetings unless they provided an acceptable excuse. Common excuses included illness and travel. Members were fined 1 shilling, about $4-$5, for each unexcused absence, which the secretary tracked in his ledger. Members were required to pay any outstanding debts prior to each St John’s day in June and December. Fines were eventually phased out by the early nineteenth century.

Article seven prohibited members from “raising angry disputes” with each other. Fines increased in severity after multiple offenses. The first offense resulted in a vocal reprimand by the master and the second resulted in a 5 shilling fine. The fine doubled to ten shillings for the third instance and the offender was “solemnly excluded” from the meeting for the night and would only be admitted again after a formal apology. Similar fines were levied for inappropriate language (article eight) and improper dress (article nine).

Article eleven covered fees and regular payments owed to the lodge. Each member was required to pay 1 shilling each month towards the lodge’s operations, which they referred to in the bylaws as “the Fund.” The Secretary collected all monies during each meeting and transferred over to the Treasurer for his deposit. Prior to the Coinage Act of 1793, which officially designated the dollar as the national currency, states issued their own currency along with foreign currencies that remained in circulation. Therefore, the lodge’s affairs were often conducted in British and colonial state issued pounds, shillings, and dollars. Today, masons can remit their annual dues payment through electronic means, which do not require their attendance to meetings.

Article 11 Describes Fees Owed to the Lodge.

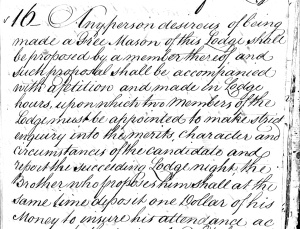

New membership is covered in article sixteen. Petitions required a single member to propose a candidate for membership. The lodge assigned two other members to “make inquiry into the merits, character, and circumstances of the candidate and report the succeeding lodge night.” Furthermore, the proposer paid the petition fee. “The brother who proposes (the candidate) shall at the same time deposit one dollar of his money (along with the petition) to ensure (the candidate’s) attendance.” This ensured that both the proposing member and candidate were serious with their intentions and financially invested in the process. Once approved, the candidate paid his initiation fee and the tiler received the petition fee – perhaps as regular payment for his duties in and outside of lodge. The candidate’s fee was returned if the lodge rejected his candidacy. The bylaws also note that if the lodge elected the candidate for membership but he later declined to proceed, the tiler would keep the dollar from the proposing brother. Today, candidates pay the petition and degree conferral fees.

Candidates paid four pounds and sixteen shillings to receive the three degrees of Freemasonry, which equates to around $835.00 in 2022, adjusted for inflation. That said, early salaries were much lower than today. A Virginia school teacher, for example, garnered around sixty to seventy pounds each year. If he sought membership to the lodge, he would spend 6-7 percent of his annual income for his initiation. Most citizens were self-employed and many worked as farmers, which garnered less than sixty pounds each year. Thus, the lodge’s membership was effectively composed of men from Alexandria’s upper-middle to upper class

Article 16 Covered the Petition Process.

Other articles covered lodge voting procedures, committee membership, and duties related to the Grand Lodge. The document ends with a list of signatures by the lodge’s earliest members, who by custom signed the book to affirm that they abide by the lodge’s rules. Articles were regularly updated, dropped, and added throughout the lodge’s history to adapt to changes in the fraternity, society, and the economy.

What do the first bylaws tell us about Alexandria lodge and Freemasonry? First, the lodge’s membership mostly consisted of upper-middle to upper class Alexandrians. Second, they took their membership seriously and imposed

fees and penalties for those who violated their obligations. Members were expected to attend each meeting, dress appropriately, and find ways to resolve conflict without devolving into anger or slander. Third, proposing a new candidate for membership required a financial commitment from the proposing brother. This ensured that both parties were serious about who would join the lodge. Fourth, members were obligated to invest into the lodge regularly, to ensure the lodge had funds to cover its expenses and distribute charity to deserving brethren and their families. These founding rules and principles enabled the lodge to proposer well into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

–

Brother Chris Ruli is a masonic researcher and historian who focuses on the history of Freemasonry. He is a member of Alexandria-Washington Lodge 22, Virginia and Federal Lodge 1 of Washington, D.C.